According to the common narrative after the Global Financial Crisis, the world’s leading central banks were the heroes that saved the day. And more recently, the central banks, especially the U.S. Federal Reserve, once again rescued the credit markets this year as the Pandemic unfolded. However, what if I told you that many economists believe these crises were actually a result of previous central bank missteps?

Stability breeds instability.

Hyman Minsky, American Economist

Introduction to Central Banks and Debt Cycles

I know many may not be familiar with the role of a central bank, so let’s start with a definition:

A central bank is a financial institution given privileged control over the production and distribution of money and credit for a nation or a group of nations. In modern economies, the central bank is usually responsible for the formulation of monetary policy and the regulation of member banks.

https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/centralbank.asp

In simple terms, a central bank manages the money supply for a country or countries and sets interest rates (i.e. the cost of money) and controls the amount of currency in circulation. The most influential central banks are the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed), European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of Japan (BOJ), Bank of England (BOE), Bank of Canada, Royal Bank of Australia (RBA), and People’s Bank of China (PBOC).

In this article, I will primarily focus on the Fed, although in many cases these issues are prevalent in most of the above-mentioned central banks.

Throughout the history of central banks, their primary mission has been price stability. In other words, central banks take actions to control inflation to keep all of the consumer goods that citizens purchase at a stable price. An economy will tend to move between periods of growth (i.e. booms) and contraction (i.e. busts). Periods of growth will start at the bottom of the business cycle, where central banks have lowered interest rates in an attempt to stimulate the economy. At the bottom of the cycle it becomes easier and cheaper for businesses and individuals to get loans. These loans are then used to reinvest in businesses and increase production. As this cycle continues and more currency is injected into the market, this creates greater demand for products and services. As this happens, prices begin to increase in response to the greater demand.

For example, in 2001, after the dotcom bust, the Fed lowered rates and provided additional liquidity to stimulate the economy. As this progressed, mortgage rates dropped lower than had ever been seen before. This stimulated demand for more houses as affordability increased, resulting in higher and higher home prices. This is an example of how greater liquidity results in inflation.

As this process occurs, and the economy gets “overheated,” and inflation rises, the central banks then start increasing interest rates to get inflation under control. However, as rates rise, the weaker companies that could survive with rates low can no longer service their debt payments at these higher interest rates, causing bankruptcies of those weaker companies. This process of the “survival of the fittest” in relation to businesses is what Joseph Schumpeter coined as “creative destruction.”

Joseph Schumpeter

(1883-1950) coined the seemingly paradoxical term “creative destruction,” and generations of economists have adopted it as a shorthand description of the free market’s messy way of delivering progress.

https://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/CreativeDestruction.html

As businesses fail, employees get laid off, resulting in a recession, where the economy contracts. This is the “bust” portion of the business cycle. When this occurs, the central bank will begin lowering rates in order to stimulate the economy back into a new growth phase.

This is the classic free market business cycle, which is probably more accurately described as a credit cycle, due to the influence of the central bank on this cycle through monetary policy.

One of the more interesting reads, if you want to dig into this topic further, is a book, Big Debt Crises, by Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater Associates, one of the largest hedge funds in the world. You can download a PDF version of the book for free at https://www.principles.com/big-debt-crises/. Ray has studied past cycles, and he has identified a pattern of small debt cycles every 7-10 years that culminate in a super debt cycle ever 70-80 years. And for those of you who read my most recent post, this research ties really well with The Fourth Turning. The last debt supercycle resulted in the Great Depression, and Ray predicts we are approaching the end of the next supercycle as we reach the climax of the next Fourth Turning.

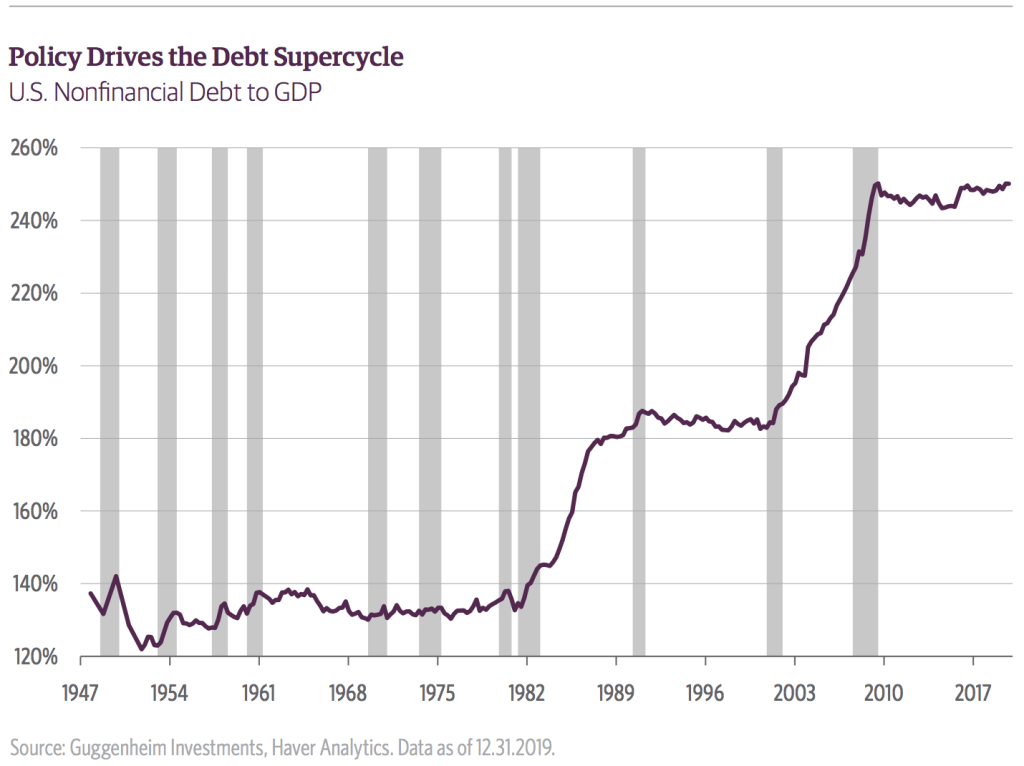

The graph below shows how this current debt supercycle has grown. The amount of debt in the economy continues to grow from cycle to cycle, until it becomes so large that it is ultimately unsustainable.

Where the Fed and Other Central Banks Have Erred

So how has the Fed erred in monetary policy? I think the cause is actually quite simple. In 1978, the Fed was given an additional mandate, in addition to the mandate on price stability: maintain full employment.

Since its creation in 1913, the Federal Reserve and its monetary policies have had a substantial impact on overall economic conditions and the labor market. With the passage of the 1978 Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (also referred to the Humphrey-Hawkins Act), the Federal Reserve was specifically required to “promote full employment and production, increased real income, balanced growth…adequate productivity growth, proper attention to national priorities, achievement of an improved trade balance […] and reasonable price stability.”

https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/full-employment-mandate-2017-07.pdf, page 1

However, when you consider this mandate in relation to the business cycle outlined above, to avoid unemployment you must avoid raising interest rates so as to avoid recessions. This is at odds with the price stability mandate, as any action to control inflation by raising rates will tend to result in and increase in unemployment.

Initially after the bill’s passage, the primary focus remained price stability.

For decades after the “Great Inflation” of the 1970’s, economists and Federal Reserve officials prioritized price stability, and even viewed full employment through the lens of what was possible to prevent inflation.

https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/full-employment-mandate-2017-07.pdf, page 13

This changed, however, in the 1990s under Fed chairman Alan Greenspan (1987-2006), who believed it was possible to keep rates low and maximize employment while keeping inflation in check. And throughout the 1990s, it worked. The economy hummed along at its best pace in 30 years, with low unemployment and inflation under control.

Unintended Consequences

However, under the surface, some unintended consequences were taking place, primarily a building asset bubble in technology stocks. This occurred due to an economy that was flush with cash, leading to increased investments in the stock market. And of course the hottest stocks were the new high-tech sector. It didn’t matter if these companies were profitable or generated positive cash flows, and the valuations became extreme, especially for an accountant like me that understood how to read a company’s financial statements. Some of you may remember these companies that crashed down to earth: Priceline.com, Webvan, TheGlobe.com, Pets.com, eToys.com, and Drkoop.com are a few examples. Even the companies that survived the crash experienced substantial drops in their valuations when the bubble eventually burst.

Low interest rates also encourage people and companies to borrow more money, in effect bringing spending forward. Let’s re-visit the graph above, and look at how debt grew after the Fed’s new mandate in 1978.

The policy of the central bank to continually step in, lower interest rates, and encourage companies and people to take on more debt has been in place since the 1930s. The idea that the central bank could push interest rates down and make more credit available to smooth out the business cycle is designed to have an economy that operates with fewer recessions, less severe recessions, and ultimately longer periods of expansion. This policy worked, but it also created the Great Debt Supercycle: Every time we get ourselves in a recession, the total debt of the U.S. economy rises relative to gross domestic product (GDP) to new and higher levels. This is not sustainable in the long run, even if we are able to push interest rates into significantly negative positions on a sustained basis.

Guggenheim Global CIO Outlook, May 10, 2020

Another unintended consequence is that these policies can artificially inflate financial assets like stocks and bonds. Who does this benefit? The rich. The top 1% richest individuals now own more that 50% of corporate stocks, and the top 10% own 88%!

https://business.financialpost.com/investing/how-americas-1-came-to-dominate-stock-ownership

So when the financial markets are artificially inflated by Federal Reserve policies, it is the rich that benefit. This is a key reason why today we have extreme wealth inequality in the United States. Take a look at this graph, and you will see that wealth inequality started increasing as The Fed’s looser monetary policies began to be implemented in the early 1990s. Even after the market declines in 2001 and 2009, the trend quickly re-accelerated.

Of course, this is not intentional.

Oh, so maybe I am wrong about that “unintentional” thing. Sorry about that.

We are now in an era where many central banks are keeping interest rates artificially low in order to avoid recessions. It all started with the Bank of Japan, where they were successful in keeping rates low without creating high inflation. However, growth has stagnated in Japan for the past 30 years. This is the path that many other central banks are now going. But keeping rates artificially low also has negative consequences. It punishes savers, especially older people on fixed incomes. The returns on safe investments such as government bonds no longer provide much of a return. The alternative is to put your investments in riskier assets in an effort to boost returns. Unfortunately, this reach for yield can end in disaster if the underlying value of these assets drop.

In addition, as debt loads increase at the government, corporate, and individual levels, growth stagnates. It is a proven mathematical fact that the Fed’s actions to drop rates are resulting in less and less effectiveness as debt loads increase.

If I wanted to think of how to destroy a country, I could not have done a better job if I’d tried. Years of zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and quantitative easing (QE) created the most inequality we have ever experienced. Then everyone is locked up for a few months, and all it takes is a spark…

I don’t spend much time criticizing the Fed. (There are enough people who have made entire careers out of that.) And it may seem like a bit of a stretch to blame the riots on the QE of 2008, but I disagree.

Monetary policy indirectly bears responsibility here. If you wanted to fix all of this overnight, it is actually very easy: Raise interest rates to 5%.

Jared Dillian, “The 10th Man – The Saddest Day Ever”, June 4, 2020 https://www.mauldineconomics.com/the-10th-man/the-saddest-day-ever

Conclusion, Part 1

We are heading for the end of a debt supercycle, which will likely end in a painful deleveraging. Has the recent pandemic led to the start of this? It is very possible, but the central banks may be able to “save us” again by “kicking this debt can down the road” for a few more years. Time will tell. Remember, the last debt supercycle resulted in the Great Depression, and debt loads as a percentage of economic output (i.e. GDP) are higher this time. As an aside, I am now reading a book, Lords of Finance, that follows the lives of the heads of the central banks of the U.S., U.K., France and Germany from the 1920s through the Great Depression. The good news is that central banks have discovered more “tools” since then to seemingly avoid a major crisis. However, the debt load continues to grow, with a huge spike in debt as a result of the economic collapse brought on by the pandemic. One of these days the party will end. The only question is when this will happen.

Thanks to all who are reading my musings. I am thrilled to report that after only a couple of weeks I have readers across the globe, including the U.S., Canada, Hong Kong SAR, China, Costa Rica, Brazil, Argentina, Germany, Czech Republic, and India. I am honored that you find these posts of interest.

As a follow-up to last week’s post on The Fourth Turning, I failed to include a link of a one hour interview with Neil Howe that is free at https://ttmygh.com/hmmminars/. The interview with Neil is #16, right at the top. You may want to check out some of the other interviews as well, with top leaders in financial markets, economics, and geopolitics. This website’s author is Grant Williams, who writes an incredible newsletter (bi-weekly, 25 issues per year). I first came across Grant’s writings about 5-6 years ago, when access to his site was free. Grant later made it a paid newsletter, and I must admit I am financially conservative (a nice way to say I’m cheap), so I initially resisted paying for a newsletter that was previously free. However, after about a year, I missed it so much that I subscribed and then read all of the issues I had missed! It is well worth the money if you want another source of material for understanding financial markets and the economy.

I hope everyone has a great week!

Best Regards,

Brent